America's Fallen Hero's

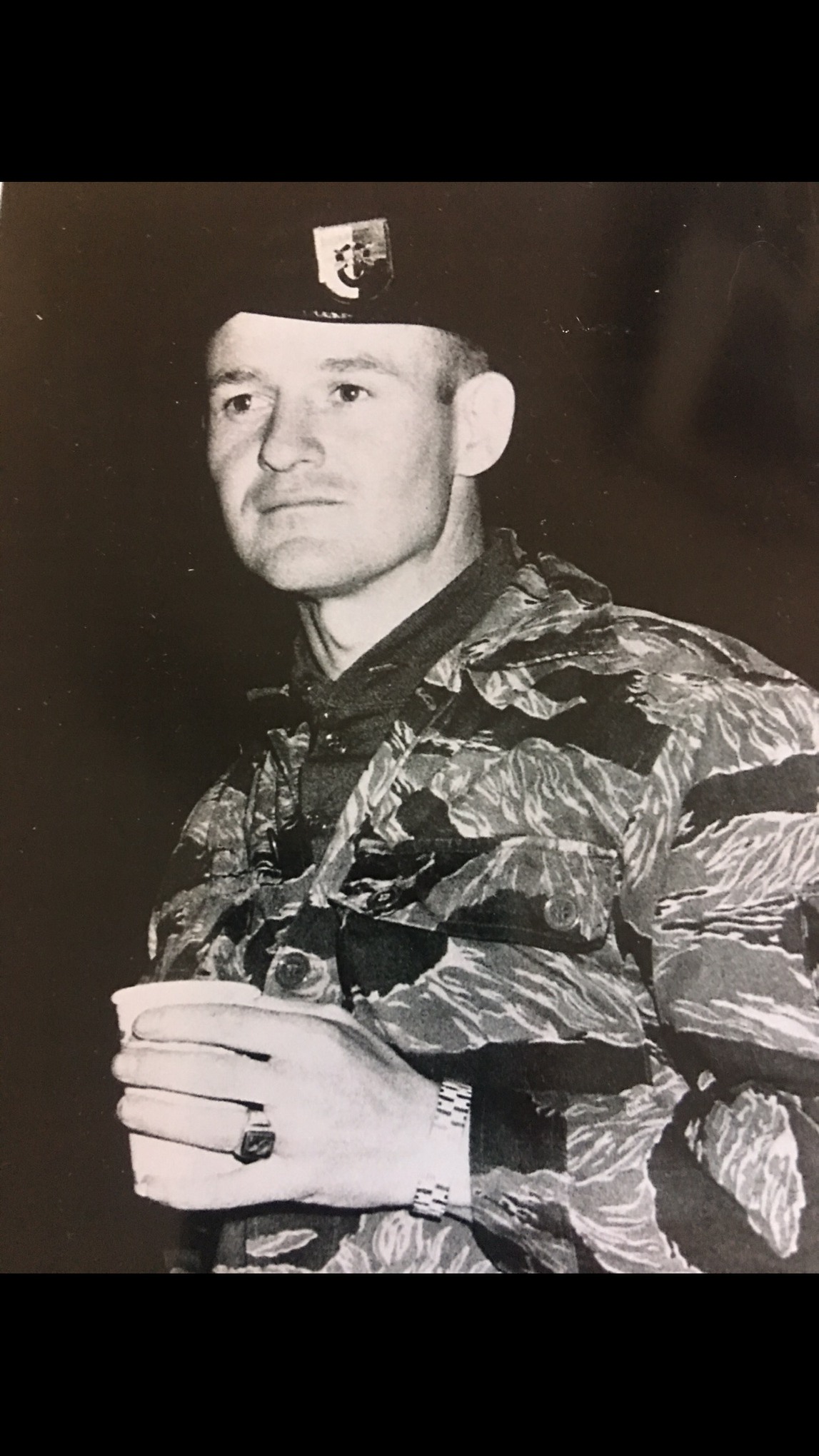

MSG Robert A. AnspachThe Special Forces camps in the Delta region of South Vietnam had been suffering loss and damage from floodwaters in late 1966. The floodwaters also severely curtailed operations conducted on foot, and the Special Forces, using airboats, and teamed up with Navy Patrol Air Cushion Vehicles (PACV) and helicopters conducted a number of successful missions over the flooded regions. During the ensuing winter dry season, the camps were improved or rebuilt to help withstand future flooding, while their garrisons trained toward improving sampan and airboat patrols during the next high water season. Despite the preparation, there were still only a limited number of Special Forces personnel and technicians familiar with airboat operations and logistics, and this activity was limited to Kien Phong ("Wind of Knowledge") Province along the flooded banks of the San Tieu Giang River. Detachment B-43 was deployed to Cao Lanh in Kien Phong Province during the dry season in February 1967, and a full-shop airboat facility was finished in May. The Viet Cong had realized the tactical potential of airboat operations, and made this facility the target of a mortar and rocket attack on July 3-4, with devastating losses to the airboat operations effort. Capt. Jeffery Fletcher's Thuong Thoi Detachment A-432 had been redesignated from A-426 on the first day of June, 1967. With the onset of floods on September 9, two airboat sections were attached to his command under Capt. Thomas D. Culp and SFC Robert A. Anspach from A-401's Mike Force at Don Phuc. They began operating out of the camp on the river near the Cambodian border close to Hong Ngu. Fletcher was concerned about his 454th CIDG Company manning a border outpost on the Mekong River and the increase in leaking that threatened the main camp berm. His camp was about to witness one of the most crippling defeats that Special Forces airboats would suffer. At 0830 hours on the morning of September 11, 1967, six airboats departed on a reconnaissance mission. Each boat carried four men, and the force included three Special Forces advisors, one interpreter, one LLDB noncommissioned officer, and ten Chinese and eight Cambodian Mike Force soldiers. SFC Robert Anspach, platoon sergeant, headed the formation in Boat 1, accompanied by LLDB Sgt. Binh, one Chinese soldier, and interpreter Chau Van Sang, who doubled as driver. Capt. Thomas D. Culp went in middle Boat 3, and the A-425 team sergeant, MSgt. James W. Lewis, occupied the last one, Boat 6. The operation was to sweep north to within a mile of the Cambodian border, then west to the Mekong River. Possibly because floodwaters had changed the appearance of the landscape, the airboats passed their intended turning point and proceeded in line down a stream to the river that formed the international boundary. The rice paddies were under six to ten feet of water, and the dry banks of the river were covered with trees and heavy brush. As the first four airboats left the stream and entered the Vietnamese portion of the river about 5 miles northwest of the camp, Viet Cong bunkers on both sides of the channel caught them in a lethal cross fire. Concentrated machine gun fire riddled all six airboats in the first burst, killing SFC Anspach immediately. This resulted in fatal confusion. Instead of trying to break out of the area at once, the column circled and doubled back to the killing zone. The lead boats were hit repeatedly. LLDB Sgt. Binh screamed at Sang to turn back, and although Sang could not hear him over din of engine and arms fire, he desperately drove Boat 1 back toward the mouth of the stream as the Chinese soldier returned fire with the machine gun. Just before the boat reached the west bank, it went dead in the water, and Sang jumped out and swam ashore. Airboat 1, containing Anspach's body, was later observed from the air being pushed and pulled across the border by the Viet Cong. Boats 2, 3 and 4 tried to execute a clockwise circle in the river, but the maneuver was ripped apart by the intensity of fire directed at them. Boat 2 plowed into the riverbank and sank. Capt. Culp in Boat 3 was shot in the left arm, crouched in the boat and returned fire at treeline with his M-79 grenade launcher. Airboat driver Than Ky Diep moved the craft back downstream, but the craft took several more rounds, and Capt. Culp was killed. The driver of Boat 4, Ly Phoi Sang, was wounded in the right shoulder. He managed to get the boat back into the stream, where it lost power. The crewmen of Boat 5 were killed or wounded in the first few seconds. Their boat drifted to the bank of the river, where it was captured. MSgt. Lewis had been wounded in Boat 6, but kept radio contact until he lost consciousness. The driver, Hoang Van Sinh, steered his boat out of the fighting, but the engine was shot to pieces, and it drifted to the stream bank. The firing had lasted two minutes. One boat had sank, two were in VC hands, and two others immobilized. Only Boat 3 was still running. The remaining airboat section raced out of Thuong Thoi under SSgt. Jackson of A-401 and SFC Pollock of A-432 and linked up with Boat 3 to collect the survivors huddled on the shorelines. Pollock reached Boat 4 and towed it back to camp. Boat 2 was later evacuated by Chinook helicopter. Airstrikes were called in to destroy Boat 5 and the bunkers on the near side of the river. Only Robert Anspach remained unaccounted for after the battle. Three reports relating to the mortal remains of Robert Anspach were received by U.S. officials from ex-Viet Cong and refugee sources. One report stated Anspach had died as a result of wounds suffered during an ambush. Another report indicated that he was buried alone, wrapped in a hammock. Other, more reliable sources claimed that he was buried in a common grave with 3 Nungs (Vietnamese who were ethnic Chinese), mistaken for Koreans by the Viet Cong. Attempts were made to recover the remains of Anspach, but enemy presence at the site frustrated the attempt. Over 20 years has past since the death of Robert Anspach. The Vietnamese resolutely deny any knowledge of his fate. They resolutely deny access to the area in which he is suspected to be buried. Tragically, Anspach lies in enemy soil, when he should be buried with the honors he deserves in his homeland. Even more tragic is the multitude of reports indicating that hundreds of Americans are still alive in Southeast Asia, still captives from the long ago war we called the "Vietnam Conflict". Anspach, his comrades say, is dead. How many others will die wondering why their country has abandoned them? |

|